Che and Me

by Mark RuddA revised version of a talk given April 10, 2008 to the Peace Studies Program at Oregon State University

THE FOCO THEORY

From the first moment I heard about Che, Ernesto Guevara, he was my man, or, rather, I was his. Brilliant, young, idealistic, a daring commander of rebels, willing to risk his life to free the people of the world, I wanted to be like him. Who wouldn’t fall for this rifle-toting poet who wrote, “At the risk of sounding ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love.”

When Che said “the duty of every revolutionary is to make the revolution,” he was ordering me directly, “Do it, don’t just talk about it!” Total commitment was needed.

When Che said “the duty of every revolutionary is to make the revolution,” he was ordering me directly, “Do it, don’t just talk about it!” Total commitment was needed.

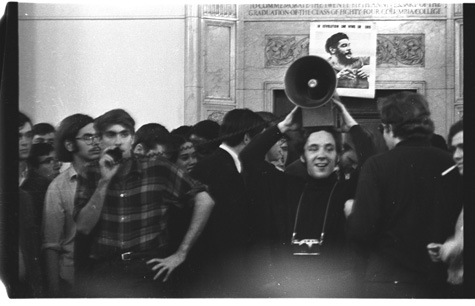

The way other leftists of the early to mid-twentieth century considered themselves Trotskyists or Stalinists or Maoists, I was a Guevarista, a member of the cult of Che. That meant not only putting up multiple posters with Che’s image on the wall in my room during college, but whole-heartedly accepting the theory that a small armed group could spark revolution by actually beginning military action. This central idea was transmitted to us via a small book which appeared in 1967, Revolution in the Revolution? by Regis Debray, a young French leftist intellectual who had conducted lengthy interviews and discussions with Che and Fidel Castro.

Foco in Spanish means nucleus, the idea being that the future revolutionary army would grow around the core of the guerilla band. Along with being called Guevaristas, followers of Che, we in Weatherman and the Weather Underground were also called foquistas. Of course our enemies on the left, which included almost everyone outside of ourselves, called us other names, such as “Third Worldists,” “left-wing adventurists,” vanguardists, “infantile leftists,” “crazies,” and much worse. We didn’t care: we knew we were right because we were with Che.

One gets the impression, viewing The Weather Underground documentary, which appeared in 2003, that there was no theory at all to our actions, that we reacted purely emotionally. Our motivation for violence, as depicted in the film, appears to have been the frustration we felt that the war didn’t end after years of protesting. I admit that there was an element of frustration in the choices we made: we had no idea at the time that the anti-war movement was actually having an enormous influence on the war planner’s policy options. With the characteristic impatience of youth, we ached to “take the struggle to a higher level.” (To learn about the actual effect of the anti-war movement on policy makers, see Tom Wells’ The War Within).

Our dominant emotion, however, was not frustration. On the contrary, it took an enormous quantity of optimism, combined with a strategic theory, to believe that this country was moving toward revolution and that our actions could play a role in that development.

Like Che, we believed that U.S. imperialism was in the process of crumbling to pieces. The military defeat in Vietnam was the prime indication of its weakness, the key to recognition that live-or-die revolution was already underway within this country and around the world. And Che Guevara’s foco theory, certified by Fidel, was the way to push it along. The revolt of black and other third-world people inside the U.S., led by the Black Panther Party, demanded white allies.

To my eternal shame, I was part of the leadership of Weatherman which scuttled SDS, the largest radical student organization in the country, in 1969, at the height of the war. A small group of less than ten people made this suicidal decision believing that with SDS dead we would be free to build an underground guerilla army, organized into focos around the country. Each foco, through its exemplary armed actions, propaganda, and contacts with the above-ground mass movement, would attract recruits to expand the incipient revolutionary army’s military capabilities, Ever Onward to Victory (Hasta la Victoria Siempre)!

One thing we hadn’t stopped to notice was that Che, in October, 1967, using precisely the same strategy that we proposed to use, had already been defeated and killed in Bolivia while trying to spark a continental revolution against U.S. neo-colonial domination. Wandering futilely around the jungle, much more alien to the campesinos and indigenous people than even the Bolivian army, his band was isolated and smashed. Che, in 1965, had tried the same strategy in the Congo in Africa, only to be driven from the continent. A guerilla foco in Argentina, Che’s own home country, had been wiped out, as would more guerilla focos in Uruguay, Brazil and several other Latin American countries. Blinded by my love and admiration for “the Heroic Guerilla,” as Fidel had dubbed Che, I didn’t want to see that there was a fatal flaw in the theory. It didn’t work.

Oddly, it was the success of the strike at Columbia University—of all places—that furnished the slim evidence which convinced my friends and me that the foco theory would work in this country. In April, 1968, the Columbia SDS chapter, a small, militant group on campus, took action in concert with a group of black students; hundreds and then thousands of white students joined us in the building occupations and the subsequent strike. Our own militancy was the key, we thought, but we willfully ignored the years of concerted organizing that had gone before at Columbia. We also didn’t acknowledge the impact on people’s psyches of a cascade of historic events that occurred in rapid succession that spring: the Tet offensive in Vietnam, the abdication of LBJ, and the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr..

I’m certainly not critical of Sam Green, the director of The Weather Underground, for omitting the foco theory from his documentary because it’s very difficult to convey complicated ideas in film. Still, I want it to be on record that we at least had a theory, or believed that we had a theory, albeit a flawed one, to justify our actions.

This particular mistake illustrates well the down-side of idealism, because that’s what we were, idealists. We believed our own ideas just because we had them and we wanted them to be true. I have a bumper-sticker on my car that reads, “Don’t Believe Everything You Think.”

WHY VIOLENCE?

I’m basically not a violent person. My whole life I’ve feared fights and contact sports. I always ran away from schoolyard fights. When I was little, my favorite book was Ferdinand the Bull, about the bull who refused to fight in the bullring, just wanting to smell the flowers. For years I’ve pondered the question of why I chose the path of violence, of armed struggle.

We were intellectuals of sorts, in SDS and the Weathermen, people who lived on ideas. Forty years ago, we were among the large number of Marxist New Leftists who held to the central notion that the world was undergoing violent revolution as a natural and inevitable response to the colonization of the third world by European and then American imperialism. That’s what the Vietnam War was about, likewise the national liberations movements in Cuba, China, Latin America, Asia, and Africa and inside this country, too. Decolonization was the hidden meaning behind the title of our central theoretical paper, “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know the Way the Wind Blows.” We were trying to tell the dogmatists and fundamentalists among us, those who held rigidly to the theory of industrial working-class revolution left over from Marx in the mid-nineteenth century, to wake up and look at the world.

Meeting Vietnamese fighters in Cuba in February 1968 and getting to know Cubans who were in the process of making their young socialist revolution, strengthened my fierce desire to support these heroic people who had taken on the greatest military power in the history of the world and were actually beating it on the battlefield!

My comrades and I recognized that imperialism imposes a violent status quo: it is a system which rules by force. From this it followed that imperialism won’t give up without a fight. Didn’t Mao Tse-tung himself write, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun?” Who were we to say differently? Cuba, China, Vietnam, the ongoing struggles in the Portuguese colonies of Africa, all showed us the way.

The Wretched of the Earth, by Franz Fanon, an explication of revolutionary violence as the means of decolonialization, was on all of our bookshelves. We accepted as gospel the psychological necessity of violence as a necessary stage of decolonization. Fanon was a brilliant psychiatrist from Martinique who treated French colonizers by day and Algerian revolutionaries by night. In those pre-feminist days, it made sense to us that the colonized and humiliated would take back their manhood through violence.

You don’t need to dig too deeply to understand the logic of revolutionary violence: it is generally accepted in most societies that it is moral to use a small amount of violence to stop a greater violence. Since the status quo is violent to millions, the antidote is pointed violence to change the balance. This view is not that different from the Christian “just war” concept, which also accepts the necessity and morality of violence. Even Buddhists tell stories about the Buddha using a sword to kill a very evil person who is about to take many lives.

It appeared to us that nonviolent strategies weren’t as effective or complete as Marxism-Leninism and revolutionary war. India had broken away from Britain using Gandhi’s nonviolence, but the impoverished, class-ridden society remained, and the people were not much better off than under the British. We preferred the radical revolutionary society of Mao’s China. Malcolm X and the black power movement, using the slogan, “by any means necessary,” had quite pointedly criticized the integrationist, more cautious politics of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the insufficiency of the nonviolent civil rights movement in the South. Black Power was radical because it held that black people were taking full power—self-determination—for themselves.

WHITE ARROGANCE

Having successfully (in our minds) united revolutionary anti-imperialism with Che’s foco theory, a role suddenly appeared for us: we would be guerillas “in the belly of the beast” (a much over-used metaphor). As white people, we would have certain advantages in mobility and access within this society that nonwhite people didn’t have. In a reverse double-whammy maneuver, we could use our white skin privilege to overthrow the structure of racist privilege. It was like being secret agents. For this reason alone we believed it was our revolutionary duty to take up armed struggle. In fact, in discussing what we were doing among ourselves, we often called our role “agents of necessity.”

From sympathizing with the armed decolonization struggles of the people of the world, it was an easy but fatal jump for us to believe that we would be racist just to cheer our heroes on, without taking any of the physical risks ourselves. The Black Power movement and the Panthers in this country were “picking up the gun,” so we concluded that white people should also, out of revolutionary solidarity. “The Politics of Revolutionary Solidarity” reads the subtitle of Dan Berger’s 2006 history of the Weatherman Underground, Outlaws in America. Unfortunately, Dan considers our words and motives more important than results. I would have preferred a subtitle “The Politics of Revolutionary Suicide.”

Fighting cops in the streets and undertaking guerilla warfare was not what the Panthers or the Vietnamese or the Cubans actually wanted or needed. In the summer of 1969, Weather people had met members of a Vietnamese delegation in Cuba who urged us to unite as many people as possible against the war. Instead we did the opposite, attacking the anti-war movement as not being revolutionary enough and organizing the Days of Rage in Chicago, in October, 1969, as a hyper-militant fight-the-cops action. Fred Hampton of the Chicago Panthers trenchantly criticized the Days of Rage as “custeristic,” while the Cubans sent word to us through informal channels that they thought the planned action was a terrible mistake.

Completely ignoring what we claimed was our “Third World leadership,” we insisted that we would be the heroes, the tough guys. I became a ranting, raving hard-core lunatic, brandishing a chair leg at the first Columbia SDS meeting in the fall of 1969, bragging to the hundreds present, many of them former friends, “I’ve got a gun! Now go get yours!” I talked incessantly during that period of the need to “get serious.” My ability to maintain this revolutionary posturing only lasted at most six months, until the act just collapsed of its own weight, thank God. By the end of the next year, 1970, I was out of the Weather Underground Organization, still a fugitive, but no longer an official cadre, or member.

In our arrogance, we had refused to look at the actual conditions within the U.S., including especially the isolated position of the Black Panthers and other non-white revolutionaries who were under terrible attack by the government’s repression. Insanely, we gave up on actually organizing other white people to supporting anti-imperialism: only we Weathermen would be the good whites. That attitude reached its highest expression in the bombings planned by a clandestine Weather collective in New York City against a non-commissioned officers’ social dance at Fort Dix. Tragically but fortuitously, the bombs went off prematurely in the West 11th Street townhouse explosion of March 6, 1970; we killed only three of our own people, not the Fort Dix civilians.

THE DEMON LOVER

For many years, I was dissatisfied with the intellectual explanation of my decision for revolutionary violence, that a combination of revolutionary anti-imperialism and the foco theory made me do it. Something was missing: these ideas alone didn’t explain my swaggering and posturing for that six month period from September, 1969 to March, 1970.

In 1989, I attended a reading at an Albuquerque feminist bookstore by the writer Robin Morgan. Fifteen years before, back in 1974, Morgan had engineered Jane Alpert’s betrayal to the FBI of my ex-wife and myself. This story I tell in full in my book, Underground. Intrigued by the title of her new book, and perversely proud that I was open to the ideas of a person who had shown herself to be a snitch, I bought and read Morgan’s, The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism. Many things suddenly fell into place.

Morgan began from the premise that all violence is terrorism, including that of men against women. Governments use violence to enforce their power and order, while revolutionaries use violence to create a new “free” state. Humans are coerced both ways.

The problem on the revolutionary side, she wrote, is that the theory of liberation coming through violence is based in an ancient patriarchal archetype, probably at least five thousand years old in the Middle East. A male hero tries to liberate the people, sometimes successfully, but more often not. The savior is killed, but his violent martyrdom eventually brings rebirth and resurrection. We live because these martyrs died for us, so we need to follow their path. Sound familiar? Jesus is within the lineage of the archetype of the male martyr and savior, though he himself didn’t utilize violence. Che Guevara, my own personal saint, fits the more common pattern of the male hero who practices liberatory violence, is martyred, but who lives again as an example.

I jumped out of my chair when I got to Che. Morgan had nailed the problem and had nailed me personally, with my desire to be like Che. My career as a Guevarista suddenly made sense: a young man who seeks to prove himself through violence, in the image of the patriarchal hero. This is not what is meant by people liberating themselves, by the advance of freedom and democracy.

In this light, the whole theory of revolutionary violence collapses as just one more form of anti-human domination. That’s why it doesn’t work. I could no longer look on any heroic revolutionaries, even the ones I liked, such as the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, as anything other than future oppressors and bullies. I finally stepped off the train of revolutionary violence.

LOOKING AT CHE AGAIN

Motorcycle Diaries, a movie depicting Che’s journeys through South America appeared almost fifteen years later, in 2004. The movie tells a great story of a rich, young Argentine doctor who discovers his own continent and awakens to Latin America’s people and problems. At one point in the film, Che even gives a speech alluding to his future direction opposing American imperialism.

Several young people, including my own daughter, saw the movie and asked me what I knew about Che. I told them about Che’s impact on my own life, highlighting the foco theory. Realizing that I had several gaps in my knowledge of Che’s life, I began a small study, reading several biographies. My favorite is Jon Lee Anderson’s encyclopedic Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. Anderson, a reporter who often writes for the New Yorker, actually moved his family to Cuba for five years and obtained access to all sorts of people close to Che and to Cuban archives. Along with Che’s revolutionary triumphs and adventures, and his thrilling theories of socialist transformation of human beings, some troubling patterns began to emerge.

All the biographies agree that Che was from a very young age an extreme physical risk-taker, possibly as a result of his compensating for his lifelong debilitating asthma. This risk-taking carried over to his revolutionary practice. His bravery and recklessness under fire was legendary. In the mountains, Che always led the attacks, rifle in hand, often in direct contradiction to Fidel’s orders. The heroic march of Che’s guerilla column to open the second front in the revolutionary war is credited with dealing the death blow to the dictator Batista’s army.

Che was a tough guerilla commander, a disciplinarian, occasionally executing his own men for possible weakness or disloyalty. Perhaps that’s what he meant in the same passage cited above about great feelings of love when he referred to the need to “make painful decisions without flinching.” Let’s look at the actual situation in more detail: an aristocratic Argentine doctor puts a gun to the head of a terrified young Cuban campesino and pulls the trigger for the good of the revolutionary cause. Granted that giving information to Batista’s army might have meant the end of the guerilla column, there’s definitely a problem here of ends and means.

When the guerillas took Havana, in January, 1959, Fidel put Che in charge of the firing squads at El Moro, the old Spanish fortress. His charge was determining who of the old order would be executed and immediately carrying out the firing squads. Che seemed to relish the job, perhaps as the agent of necessity, but who’s to say that there wasn’t some other reason?

Che eventually became director of the Cuban central bank, taking charge of economic and industrial development. He was sent on several extended international diplomatic missions, meeting with the leaders of China, Egypt, Indonesia and other Third World powers. But it was the life of the guerilla which he always craved: he needed a gun in his hand. Che chose to leave Cuba in 1965 to fight clandestinely in the Congo, an adventure which proved a total rout. In 1966 he led the doomed guerilla column into the Bolivian jungle. By the next year he would be dead.

This is a tough thing to write, since it puts me close to the camp of right-wingers who have always attacked Che as a murderer and a terrorist, but I believe that by the end of his life, after the years of blood and to-the-death struggles of the Cuban revolution, Che had become both homicidal and suicidal. He clearly knew he was going to die in Bolivia when he left behind the following message, which thrilled me as a twenty year-old when I first read it:

Wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome, provided that this, our battle cry, may have reached some receptive ear, and another hand may be extended to wield our weapons and other men be ready to intone the funeral dirge with the staccato singing of the machine guns and new battle cries of war and victory.”

Che created a poem out of violence, “the staccato singing of the machine guns and new battle cries of war and victory.” Rereading this passage as a middle aged man, it chills me. I don’t find it quite so alluring as I did when I was a kid.

Of course, Che’s life was much more complex than I’m making it out to be. He was a utopian who claimed to have established altruism in place of material incentives in Cuba’s economy, a huge step on the way to creating the “new socialist man.” Che himself was extolled as the model revolutionary, volunteering to harvest sugar on his one day off, never once taking a perk that brought him above other Cuban citizens. He is said to have been incorruptible. It was recounted that he wouldn’t allow his wife to take their sick kid to the hospital in the government vehicle assigned to him as a minister and comandante, so she had to take the bus with the child. He continually volunteered for extra physical labor, despite his asthma. Che, for fifty years, has been Cuba’s disciplined, aescetic, revolutionary model. Generations of Cuban kids have been exhorted vivir como el Che, to live like Che.

When George W. Bush in 2006 went to a Latin American summit in Argentina, Che’s home country, fifty thousand people welcomed the Butcher of Baghdad with giant pictures of Che. For millions around the world, Che is the most powerful symbol of resistance to U.S. imperialism. There’s no way that I would want to change that, but personally, I’ve long ago opted out of the cult of Che which I joined over forty years ago.

It’s impossible for me to look on Che as the great revolutionary hero anymore; for me there are no more heroes, nor are there saints.

To the extent that I got caught up in the cult of Che, and wanted to be a hero like him, I hold only myself responsible. It’s taken me a long time to realize that we don’t need great revolutionary heroes—they actually get in the way—but ordinary people taking countless small acts such as talking to their neighbors in order to create the mass movements we need for social change.

PRACTICAL NONVIOLENCE

In 1989 I attended a talk in Albuquerque by the Dalai Lama. He was asked by a member of the audience why he didn’t hate the Chinese, who have occupied and brutalized Tibet since 1949. (Note that there’s a significant faction of Tibetans who want to fight, to resist Chinese occupation and cultural genocide with arms and blood. The Dalai Lama has been successfully cooling them out for years).

His Holiness replied, simply, “They’re our neighbors, and we’ll have to live with them when this is all over.”

My view of nonviolence is equally simple: it’s the only strategy that works. In the twentieth century alone, we’ve seen, as a result of nonviolent campaigns, the fall of the British Empire in India, the end of legal segregation in the American South, the fall of the Soviet Empire in Eastern Europe and central Asia, the fall of the Shah of Iran, Pinochet in Chile, as well as numerous global social revolutions, including the liberation of women and gays.

Mao Tse-tung was wrong when he said that political power grows out of the barrel of a gun. Coercive power is brittle; real power is consensual. This fact is equally true for revolutionary violence as it is for state violence. Since it is coercive, it will not produce the changes we want, which can only be done by consensus. Ultimately, the ruled have the power to say no. No regime was better armed against its own people than that of the former USSR. Stalin’s reign of terror had lasted for three generations. Yet in the long run, the military could not fire against civilians in 1989 and 1991, after the communist system had lost its legitimacy.

In this country the government has a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. There is no such thing as “revolutionary violence” here because people are taught from an early age that any violence that is not state-sanctioned is either criminal or insane. The Weather Underground’s symbolic bombings were never understood by the great mass of the public as anything other than that, criminal and/or deranged. Conversely, arbitrary state violence, such as the murder of Black Panthers in their beds, was considered as being both legitimate and acceptable.

The government tried to use Weatherman’s puny violence as a means of labeling the entire anti-war movement “terrorist.” We lost our moral superiority over the real murderers, the ones with enormous bombs weighing up to ten thousand pounds, delivered by giant B-52’s. The French playwright, Jean Genet, when asked about the Weathermen in 1970, sensibly answered, “The Weathermen have little bombs, the United States has big bombs,” but that was much too logical for most Americans to understand.

Nonviolent strategy—with tactics ranging from educational forums, to petitions, to electoral politics, to mass civil disobedience—is the only strategy which has a chance of working in this society. Everything else is suicide, as the example of the Black Panthers, who took up the gun for self-defense of black people, tragically proved.

Centered in the northwest ecotopia, there’s a small cult of very idealistic people who talk about taking direct action to save the planet or to rescue animals from human exploitation. The analogy to necessary sabotage against Nazi genocide is commonly made. Occasionally people actually burn a few pickups, as in the case of Jeff “Free” Luers in Eugene or they liberate some rabbits who are about to be tortured in laboratories.

The government then smashes these essentially moral and conscientious activists as criminals and terrorists, putting them away in prison for a long time. Jeff Luers is currently serving a twenty year term. That’s not even the biggest loss in this tragedy: ordinary Americans, trained to revile all violence not sanctioned by the government, including violence against property, look at these incredibly idealistic people not as the martyrs for a cause that they are, but as insane or criminal terrorists. The opportunity to build a mass movement to save the planet or free animals from bondage has been lost or set back.

Our goal is always to build mass movements for social change. In my own short sixty years I’ve witnessed or participated in history-making movements such the black civil rights movement in the south, the movement to stop the War in Vietnam, the women’s movement, the gay rights movement, the movement of disabled people for rights. Only mass movements work. That’s why they’re called movements, they’re movements of history. And mass movements are made up of millions of regular people, not heroes, who sometimes take small and mundane actions like getting their neighbors to vote, sometimes big and brave actions like sitting down in the streets to block the loading of Stryker vehicles onto ships in the Port of Tacoma bound for Iraq.

THE ORGANIZING MODEL

When I arrived at Columbia University as an eighteen year-old freshman in 1965, I was lucky to fall in with a group of young people who were organizing against the war in Vietnam using a remarkable and effective strategy which had been proven in the labor and civil rights movement. I call it the organizing model. Its goal was the creation of a powerful mass movement which can change governments, laws, and social norms. Its method was personal engagement between people—talk, sharing experiences and ideas, getting to know each other, creating community. Confrontation and big demonstrations came later, out of the existence of a base of support and in turn helping to build that base further. But the touchstone was always the question, does a given action help build the movement?

My own history went astray when my friends and I in Weatherman substituted existential politics—look at me, this is what I believe and I’m willing to act on my beliefs, so join us—for the organizing model. That led to certain isolation and defeat. People don’t join a movement because they see someone taking action, whether it be blowing up the Pentagon or standing with a sign outside a post office.

I suggest that our job now is to rediscover and recreate the old organizing model, which of necessity is democratic and nonviolent.